The Sword of Tiberius

In the collections of the British Museum in London under the inventory number 1866,0806.1, there is a very interesting Roman sword – a gladius – which, thanks to its rich and beautifully executed decoration, has attracted great attention among researchers focused on Roman military and art. The weapon was named "the Sword of Tiberius" shortly after its discovery, in reference to the second Roman emperor, and under this name, it is still known (not only) in the scholarly literature today. However, the interpretations of the historical reliefs on the scabbard of this sword are not entirely consistent among researchers in all aspects, and therefore the legitimacy of this naming has been questioned in the past.

The circumstances surrounding the discovery of this weapon are already somewhat controversial. The so-called Sword of Tiberius was unearthed on August 10, 1848, in Mainz, Germany. In the first comprehensive treatise on the sword published by L. Lersch, it is stated that the sword was found by an art and antiques dealer, Josef Gold, in a field near Mainz.(1) However, this information is incorrect. It was a deliberate lie that Gold used to cover for his suppliers and the true finders. Only later did the true circumstances of the discovery come to light. The sword in its scabbard was found by workers during the construction of a railway, in mud and sand, in a ditch in the area between today's Rheinstraße and Am Winterhafen streets. The workers then sold it to the dealer Gold. Later, after the true circumstances of the sword's discovery were revealed, the site was re-examined in greater detail, and a broken part of the sword's hand guard was additionally uncovered.

The subsequent fate of the weapon between the years 1851 and 1866 is known only fragmentarily. For a short time, the sword was in the possession of a certain von Roessler from Wiesbaden and during this period it was kept in the Wiesbaden museum for some time. Later (perhaps from 1852), the weapon was owned by one of the most well-known English antique dealers of the time, Henry Farrer. During this period, the sword was exhibited several times at art exhibitions in Great Britain. After Farrer's death in 1866, the sword was sold at auction and came into the possession of the English lawyer and art collector Felix Slade. Slade donated it to the British Museum in the same year, and it remains in its collection to this day.(2)

We have at our disposal the blade, the front part of the scabbard with fittings, and part of the hand guard. This is a Roman short sword – a gladius – of the Mainz type. After the introduction of the gladii into Roman armament around 225–200 BC, these swords continued to evolve over the years. The original so-called gladius hispaniensis was double-edged slightly waisted and had a long, tapering point. It was usually around 65 cm long and roughly 4–6 cm wide. This sword gradually evolved into the Mainz-type gladius, which resembles the shape of the gladius hispaniensis, but was generally much shorter (blade length between 42.5 to 59 cm, width between 3.6 to 7.5 cm). The Mainz type was used towards the end of the 1st century BC and especially in the 1st century AD. It was followed by the Pompeii-type gladii, which were even shorter (blade length between 37.5 to 56.5 cm), narrower (blade width between 3.5 to 7 cm), and significantly different in shape. The blades now had parallel edges and short points. Additionally, other types of swords gradually appeared in the armament of Roman soldiers, including long, originally cavalry swords known as spathae, and ring pommel swords.(3)

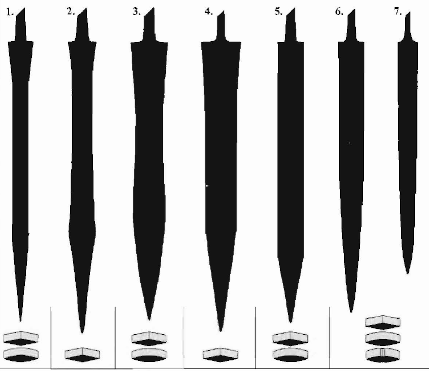

The so-called Sword of Tiberius thus belongs to the Mainz type and further to the Fulham variant, which Ch. Miks characterizes as follows: "In all cases, the blade has almost horizontal shoulders. The outlines of the edges usually narrow noticeably in the first third of the blade, run almost parallel or slightly conical toward the tip in the middle third, and then usually transition at an angle with only a slight rounding into an elongated point with mostly straight edges. The blades typically have a diamond-shaped cross-section."(4) The blade of the so-called Sword of Tiberius does not have horizontal shoulders, but otherwise, it corresponds to this definition. The total preserved length of the sword is 57.4 cm, the blade length is 53.3 cm, the preserved length of the tang is 4.1 cm, and the blade width is 7 cm.(5) The blade has a diamond-shaped cross-section.

Mainz-type gladii variants according to Ch. Miks: Studien zur römischen Schwertbewaffnung in der Kaiserzeit, Rahden, 2007.

Mainz-type gladii variants according to Ch. Miks: Studien zur römischen Schwertbewaffnung in der Kaiserzeit, Rahden, 2007.1. Mühlbach, 2. Sisak, 3. classic, 4. Fulham, 5. Wederath, 6.-7. Haltern-Camulodunum

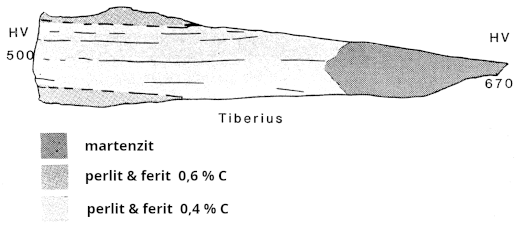

Metallographic analysis showed that the blade was forged by layering two harder strips of higher carbon steel around a core of softer, lower carbon steel. Interestingly, the edges of the blade were subsequently ground down to such an extent that the outer harder layers were completely removed in this part. The blade was then quenched to increase hardness, resulting in a sword with hard cutting edges and a tough core.(6)

Metallographic analysis of the so-called Sword of Tiberius, Lang, J.: Study of the Metallography of Some Roman Swords, Britannia 19, 1988, p. 199–216.

Metallographic analysis of the so-called Sword of Tiberius, Lang, J.: Study of the Metallography of Some Roman Swords, Britannia 19, 1988, p. 199–216.

A metal plate covering the part of the hand guard facing the blade has also been preserved. It is oval in shape, measuring 8 x 3.8 cm, and is made of bronze. The hand guard, hand grip, and pommel have not survived. These parts were usually made of organic materials, which is why archaeologists only rarely find them. The hand guards and pommels of Roman swords from this period were typically made of wood (or sometimes bone or ivory) with a spherical or lenticular shape and a circular or oval cross-section. The hand guard often had a truncated top with a bronze or iron plate fitted on the blade side. The hand grip was usually made of bone (but could also be wooden or ivory), featured four grooves or at least indicated finger separators, and typically had a hexagonal or octagonal cross-section (but sometimes also circular or slightly oval). In some cases, the grooves were absent, and instead, the hand guard was incised with a longitudinal or spiral design. Occasionally, the hand guard, pommel, and hand grip could be plated. The hand guard, hand grip, and pommel were placed on the sword's tang and secured with a peen block or top nut.(7)

Almost the entire scabbard of the sword has also been preserved. The scabbard is 58.5 cm long and 8.7 cm wide. The missing core of the scabbard was made of wood, which was covered on the front, visible side with a thin bronze sheet, tinned over the entire surface. At the top is a bronze locket plate with a historical relief (8 x 6 cm). Below it is the first bronze suspension band (9.7 x 1.4 cm) with two suspension rings (diameter 2.2 cm) for attaching to straps and a belt, beneath which is a damaged bronze plate adorned with two bands of oak leaves (7 x 4.2 cm). This is followed by a second suspension band with suspension rings and a decorative plate featuring oak leaves. Below it, in the middle section, is a circular bronze medallion with a male portrait, framed by a laurel wreath decoration (diameter 5.3 cm). Further down is a third decorative plate with oak leaves, and at the tip of the scabbard is a bronze chape with relief decoration. The lower part ends with a bronze terminal knob at the bottom. The core of the scabbard was framed on the sides by a thin metal binding, of which only small remnants have been preserved.(8)

The central motif of the relief on the locket plate of the scabbard features two main figures in the foreground. The first is a young military commander standing on the left. He is dressed in a tunic, muscle cuirass with pteruges, a military cloak (paludamentum) draped over his left shoulder, wearing low boots, and holding a small Victoria, the goddess of victory, in his right hand, which he is handing to the second main figure of the scene.(9) The small winged Victoria holds a palm branch in one hand and a victory wreath in the other (both symbols of victory and typical attributes of the goddess Victoria), extending it toward the second main male figure. This figure is seated on a throne, turned toward the commander, receiving the Victoria with his right hand while resting his left hand on a circular shield inscribed with FELICITAS TIBERI(i)(10) (Tiberius' fortune). The chest of the figure is naked, with only the lower part of the body covered by draped clothing that also wraps around the left arm. The depiction and posture of the seated man are reminiscent of scenes typically used at that time in artistic monuments to represent the chief Roman deity, Jupiter.

Relief on the locket plate of the Sword of Tiberius

Relief on the locket plate of the Sword of TiberiusTaken from the British Museum website

In addition to the main figures, the relief also depicts two other figures. On the far right, behind the seated man, there is a winged female figure dressed in richly draped garments, holding a scepter or spear in her right hand and a shield inscribed with VIC(toria) AVG(vsti)(11) (Victory of the Emperor/Augustus) in her left. Unfortunately, the head and part of this woman's body are missing due to damage to the metal. In the background, between the two main figures, stands a bearded man wearing a helmet and armour, holding a shield in his left hand and a spear in his right.

The relief on the tapering chape of the sword is divided into two sections by a horizontal band. In the upper section, there is a building with four columns topped with Corinthian capitals and a triangular roof, which has an arch in its central part. The roof is adorned with "pincer-like" decorations. In the center of the building stands an eagle with widely spread wings, holding a string of pearls in its beak. On either side, between the columns, are poles decorated with circular objects. In the lower part of the relief, there is a female figure dressed in richly draped garments that reach above the knees. She wears a Phrygian cap on her head, boots on her feet, and a short cloak over her shoulders. In her left hand, she holds a spear, and in her right, a double-edged axe.

Relief on the chape of the Sword of Tiberius

Relief on the chape of the Sword of TiberiusTaken from the British Museum website

As previously mentioned, scholars are not entirely unified in their interpretation of the two reliefs. The main debate centers around the identification of the two principal figures on the relief of the locket plate, but there are also minor disagreements concerning other aspects of the decorations. The reliefs are generally too small and not detailed enough to allow for identification of the figures based on typological similarities with well-known, clearly identified personalities. Therefore, most historians rely on contextual information in their attempts to determine the identities.(12) The prevailing view in the scholarly literature is that the seated figure, resembling Jupiter, is the second Roman emperor, Tiberius. This identification is primarily supported by the inscription on the shield (FELICITAS TIBERI) upon which the figure leans. The importance of this figure is also expressed by its size—despite being seated, it almost reaches the same height as the standing figure of the commander beside it. Considering other clues on the reliefs and historical context, the commander handing the small Victoria—the symbol of military victory achieved by him for the emperor and the Roman people—to Tiberius is identified as Tiberius's nephew and, from 4 AD, his adopted son, Germanicus.(13) There is almost universal agreement in the identification of the remaining two figures on the locket plate. The winged woman to the right of the emperor is the goddess of victory, Victoria. Her presence, along with the inscription on the shield (VIC AVG) she carries, again symbolizes the victory achieved by Roman armies under the auspices and supreme command of the emperor. The bearded, armed man in the background between Tiberius and Germanicus is the god of war, Mars.(14) Many go even further and add the epithet Ultor (the Avenger) to Mars, referencing the avenging of past wrongs.

The entire scene most likely relates to the years 16/17 AD. At that time, the young Germanicus had successfully concluded his campaign in Germania, returned to Rome, and celebrated a triumph "over the Cherusci, Chatti, Angrivarii, and other tribes dwelling in the regions as far as the Elbe." During the engagements fought between 13 and 16 AD, he managed to defeat the barbarians in major battles at Idistaviso and of the Angrivarian Walls, captured Thusnelda, the pregnant wife of Arminius, the Germanic leader and victor from the Teutoburg Forest, recovered two of the three eagles lost in that same battle, visited the site of the disaster, and buried the remains of the fallen. Thus, he avenged and rectified the dreadful Varian defeat of 9 AD.

This interpretation is said to be supported by the scene in the upper field of the scabbard's chape on the so-called Sword of Tiberius. The eagle in the center of the building and the decorated rods on the sides are believed to represent the recovered Roman standards. Some have identified the building itself as the Temple of Mars Ultor in Rome, where the recovered military standards were traditionally placed.(15) However, the Temple of Mars Ultor along with the military insignia is depicted on several Roman coins, and the building on the scabbard of our sword does not resemble it at all. K. Klein and J. Becker believed that there might have been two temples dedicated to this deity in Rome. The older sanctuary was located on the Capitoline Hill, while the later one was built by Augustus on the Forum of Augustus. The two scholars therefore suggest that the coins depict the Capitoline temple, while the scabbard shows the temple on the Forum.(16) However, this is far from certain. On the coin, we can also observe how Roman military standards (aquila and signa) were typically depicted in Roman art (especially in such a small format). Again, there is not much resemblance to the decorated rods on the upper relief of the chape. Some researchers have therefore suggested that the rods on either side of the eagle in the chape's relief are not legionary signa, but rather displayed military decorations—torques—as seen, for example, on the shoulders of Marcus Caelius on his tombstone.(17) Other scholars have also suggested that the building might be a sacellum—a shrine in Roman military camps where military standards were kept.(18)

Coin with the depiction of the Temple of Mars Ultor

Coin with the depiction of the Temple of Mars Ultor

A less common and convincing interpretation of the sword’s relief decoration is based on the theory that identifies the female figure with the double-bladed axe on the chape as the personification of the subjugated nation of the Vindelici (a Gallic tribe that inhabited the area of present-day Augsburg in Germany). In Horace's Odes, we find the following verses:

Videre Raetis bella sub AlpibusDrusum gerentem Vindelici, quibus

Mos unde deductus per omne

Tempus Amazonia securi

Dextras obarmet, quarere distuli

Nec scire fas est omnia...

Thus the Vindelicians saw afar

Drusus beneath Rhaetian Alpes maintaining war,

Whose custome how derived from all ages;

Their hands with Amazonian axes gages,

I have deferred to enquire of yet,

(Nor is it, to know all things, a thing fit.)

(Hor. Carm. IV. 4. 17–22; original translation by Henry Rider amended by the author of this article)

It was known in antiquity that the Amazons fought with double-bladed axes, hence the "Amazonian axe" (Amazonia securis) in this context refers to a double-bladed axe. This corresponds with the depiction on the so-called Sword of Tiberius, and we also know that Tiberius, together with his brother Drusus, fought in 15 BC (before he became emperor) against the Alpine tribes, including the Vindelici. According to this theory, the sword's decoration celebrates Tiberius' and Drusus' victory in this war, rather than Germanicus' triumph over the Germans. If this interpretation is correct, then the identity of the main figures in the scene must be reconsidered. The seated man would have to be the first Roman emperor and Tiberius' and Drusus' stepfather Augustus, while the commander bringing victory to Rome would then be Tiberius(19), or possibly Drusus(20). The shield with the inscription FELICITAS TIBERI, against which the emperor leans, is meant to serve as a gift from the emperor to the commander in thanks for the success achieved, and thus the inscription does not refer to the seated figure but rather to the figure of the commander. Conversely, the inscription VIC AVG on the shield held by the standing Victoria in the background is directly linked to the seated emperor and should be interpreted specifically as the victory of Octavian Augustus, rather than as a general reference to the victory of the reigning emperor (after the death of Octavian Augustus, subsequent Roman emperors also bore the title Augustus and were often referred to as such in inscriptions).(21)

There are also slightly different interpretations regarding the depiction of the female figure with a double-bladed axe in the lower part of the sword’s chape. E. Künzl pointed out that a figure resembling an Amazon, armed accordingly, could also reference an Oriental nation or region. This would again align well with Tiberius, who in 20 BC reclaimed military standards from the Parthians in the East, which had been lost in previous battles with this nation (particularly in the battle of Carrhae and during Mark Antony's Parthian campaign), an event commemorated on the cuirass of the statue of Augustus from Prima Porta.(22) However, Künzl also cites examples where the double-bladed axe appears on monuments associated with the Celts, and therefore agrees that interpreting the figure on the Sword of Tiberius as a reference to the campaign against the Raeti and Vindelici seems fitting.(23) There have also been suggestions that while associating this scene with the Vindelici is correct, it should not be in the sense of a defeated nation over which victory was achieved. In that case, the figure would assume a completely different posture—mourning, submissive, kneeling/sitting—as can be seen in other similar depictions. Instead, it could be a reference to the Vindelici as an allied nation, which would better align with the context of Germanicus' campaign in Germania, during which the Vindelici assisted as allies of Rome.(24)

Just as there is no absolute consensus on the interpretation of all aspects of the above-mentioned reliefs, opinions also differ regarding the identity of the man depicted in the medallion portrait at the center of the scabbard. Here too, given the context, Tiberius or Augustus are predominantly considered.(25) In this case, however, the majority of scholars (including some who identify Tiberius on the locket plate) lean more towards it being a portrait of Augustus.(26) In this context, K. Dahmen pointed out that the man in the medallion is wearing a laurel wreath on his head, not a radiate crown (corona radiata), which, at the beginning of the Roman Empire, often adorned the heads of deceased and deified emperors, including Augustus, on coins. If Tiberius and Germanicus are indeed depicted on the locket plate, and the sword was therefore made to celebrate Germanicus' victories (i.e., after Augustus' death), this could be an argument against the medallion being a posthumous portrait of Augustus.(27) Alternatively, it might be an argument for favoring Augustus as the main figure on the locket plate.(28) However, T. Hölscher has pointed out several examples of posthumous depictions of Augustus with a laurel wreath on Roman coins, therefore we should not draw any definitive conclusions from this aspect.(29)

Relief on the medallion on the so-called Sword of Tiberius

Relief on the medallion on the so-called Sword of Tiberiustaken from the British Museum website

The oak branches on the three decorative plates of the scabbard likely represent the coronae civicae.(30) The corona civica (civic crown) was one of the highest Roman military decorations. It took the form of a wreath made from oak twigs and leaves and could be awarded under certain conditions to a Roman citizen who saved another Roman citizen in battle.

In any case, the decoration of the so-called Sword of Tiberius is beautiful and elaborate. At the time of its discovery, material analyses had not yet been conducted, and some scholars, judging solely on appearance or reports from colleagues, believed that the scabbard was made of silver or at least silver-plated, and the decorative fittings were made of gold (or gilded).(31) Because of this, the sword received enormous and enthusiastic attention from the scholarly community of the time, leading to rather bold theories regarding the sword's origin and purpose. L. Lersch speculated that the sword might have been commissioned in several copies by Germanicus as a gift for his closest military commanders.(32) A similar idea—that the sword was a gift to army officers from Tiberius or Germanicus—was proposed by J. Gagé.(33) F. Ritter guessed that the sword might have been commissioned by the Senate, which then sent it to Mainz to serve as decoration in one of the main representative halls of the local legionary camp.(34) T. Bergk suggested that it was an honorary gift from Emperor Augustus to Drusus.(35) K. Klein and J. Becker believed that the sword was likely given by Augustus to Tiberius for his victory over the Vindelici (achieved together with Drusus).(36)

Today, our knowledge has advanced. We now know that no precious metals were used in the sword.(37) We also know that elaborate decoration on Roman swords, daggers, and other weaponry was not uncommon. This is evidenced by new discoveries of Roman militaria, as well as numerous depictions on gravestones and other monuments. On Roman sword scabbards, we find a wide range of more or less extensive and more or less intricate designs—from complex geometric or plant motifs, to numerous and diverse figurative motifs (Victoria, Mars, Roma, soldier, captive, etc.), animal motifs (she-wolf, dolphin, eagle, hunting scenes, etc.), and various additional related depictions (tropaion, weapons, signa, lightning bolts, victory wreaths, etc.).(38) In this regard, the so-called Sword of Tiberius is certainly not unique. H. Klumbach also pointed out that the reliefs on both plates of the scabbard were not hammered but stamped using a prepared mold, suggesting that the so-called Sword of Tiberius was not a unique item made to order, but probably just one of a series of more or less mass-produced items.(39) E. Künzl believes that the decoration on the building with the eagle on the scabbard's chape shows elements typical of Mainz provincial art, which would suggest that the sword itself was also made in the border province rather than in Rome.(40) Following this, Ch. Miks speculated that these swords were probably not distributed throughout the entire Roman Empire but were likely limited to parts of the army on the Germanic frontier that participated in Germanicus's campaigns, or even to certain soldiers only.(41) However, whether the building's decoration is really typical for Mainz art is debatable.(42)

In any case, all evidence suggests that the so-called Sword of Tiberius was not an exceptionally rare or unique weapon in its time, as previously thought, and it is unlikely that it belonged to anyone from the imperial family. In this regard, we have another interesting detail at our disposal. On the back of the locket plate, an inscribed name was found: AVRIILI. Similar inscriptions on Roman weaponry are fairly common and typically denote the owner of the item.(43) Unfortunately, we have no further information about this man, Aurelius. Based on the above, it can be assumed that he was a soldier, perhaps an officer, who served in Mogontiacum (Mainz) sometime after 16 AD.(44)

Regardless of the significance or insignificance of the owner, the decoration on the scabbard of the so-called Sword of Tiberius presents a fascinating example of Roman visual state propaganda. In this context, one typically thinks of large state monuments (triumphal arches, columns, temples, statues, and their reliefs) and, of course, coins or gems. However, as early as the beginning of the principate, propaganda also began to appear on military equipment—particularly on sword scabbards and the fittings of military belts. In this regard, V. von Gonzenbach identified three main thematic categories on swords and belts during the Tiberian period. These include state mythology (typically motifs of the she-wolf nursing Romulus and Remus, various deities of the Roman pantheon—especially Roma and Victoria, etc.), the theme of the emperor bringing good fortune (primarily cornucopias, globes), and historically oriented scenes (symbols of victories and triumphs—tropaion, weapons, captives, historical figures).(45) In the message of the relief on the locket plate of the so-called Sword of Tiberius, we can see a perfect combination of all three of these themes. It is a historical scene in the narrower sense, referring to a specific Roman victory that took place under the patronage of Roman gods, represented here by Mars and Victoria, and the unequivocal inscription FELICITAS TIBERI recalls the emperor's good fortune, which extends to the entire Roman Empire, ensuring its success and prosperity.

It is no surprise that the propagandistic visual motifs on military equipment are largely the same or similar to those used in other contemporary communication media (primarily on coins and sculptures). In connection with the decoration of the scabbard of the so-called Sword of Tiberius, particular attention has been drawn to a scene on a cameo that is very similar in meaning and composition, now housed in the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna and known as the gemma Augustea.(46) The traditional (although not necessarily universally accepted) interpretation identifies the seated male figure with exposed chest on the right side of the upper relief as emperor Augustus. The seated figures on both artistic artifacts essentially adopt the same pose and are very similar. The man descending from a chariot in the far left part of the cameo is identified as Tiberius, and the youth in cuirass standing before him is either Tiberius’s brother Drusus or his adoptive son Germanicus. They are accompanied by deities of the Roman pantheon (most likely Victoria, Roma, Oikúmené, Tellus/Italia, Neptune/Oceanus). The lower scene on the cameo depicts the erection of a victorious monument after a battle won, and foreshadows the triumph shown in the upper scene.

Gemma Augustea

Gemma Augustea

There are disagreements among scholars regarding both of the historical reliefs, and differing interpretations have emerged. Regardless of these differences, the fundamental idea and core message in both works of art remain the same. It is a celebration of Roman military victories, a celebration of the emperor and the imperial family, and an emphasis on succession, continuity, and stability within the ruling dynasty. These are messages that the state propagated in various ways within the civil and, of course, the military spheres.

The so-called Sword of Tiberius and a replica of the sword

The so-called Sword of Tiberius and a replica of the swordthe photo of the original taken from the British Museum website

References:

Becker, J.: Drusus und die Vindelicier, Philologus 5/1, 1850, 119–131.

Berkg, T.: Schwert des Tiberius, BJ 14, 1849, p. 185–186.

Bishop, M. C.: The Gladius. The Roman Short Sword, Oxford/New York, 2016.

Bishop, M. C. - Coulston, J. C. N.: Roman Military Equipment: From the Punic Wars to the Fall of Rome (2nd edition), Oxford, 2006.

Boppert, W.: Militärische Grabdenkmäler aus Mainz und Umgebung, Mainz, 1992.

Boschung, D.: Schwert des Tiberius, in: Naumann-Steckner, F. - Trier, M. (eds.), 14 AD – Römische Herrschaft am Rhein, Köln, 2014, p. 148–151.

Dahmen, K.: Untersuchungen zu Form und Funktion kleinformatiger Porträts der römischen Kaiserzeit, Münster, 2001.

Domaszewski, A. von: Die Religion des römischen Heeres, Westdeutsche Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Kunst 14, 1895, p. 1–124.

Drexel, F.: Ein Architekturmotiv, Germania 9, 1925, p. 35–39.

Gagé, J.: La Victoria Augusti et les auspices de Tibère, Revue Archéologique 32, 1930, p. 1–35.

Gonzenbach, V. V.: Tiberische Gürtel- und Schwertscheidenbeschläge mit figürlichen Reliefs, Helvetia Antiqua. Festschrift Emil Vogt, Zürich, 1966, 183–208.

Hölscher, T.: Victoria romana: archäologische Untersuchungen zur Geschichte und Wesensart der römischen Siegesgöttin von den Anfängen bis zum Ende des 3. Jhs. n. Chr., Mainz, 1967.

Klein, K.: Schwert des Tiberius, Philologus 6, 1851, p. 105–111.

Klein, M. J.: Römische Schwerter aus Mainz, in: Klein, M. J. (ed.), Die Römer und ihr Erbe. Fortschritt durch Innovation und Integration, Mainz, 2003, p. 43–54.

Klein, K. - Becker, J.: Das Schwert des Tiberius, Abbildungen von Mainzer Alterthümern 2, 1850, p. 3–33.

Klein, K. - Becker, J.: Nachtrag zu II. Schwert des Tiberius, Abbildungen von Mainzer Alterthümern 3, 1851, p. 17–26.

Klumbach, H.: Altes und Neues zum „Schwert des Tiberius“, Jahrbuch RGZM 17, 1970, p. 123–132.

Künzl, E.: Dekorierte Gladii und Cingula: Eine ikonographische Statistik, JRMES 5, 1994, p. 33–58.

Künzl, E.: Gladiusdekorationen der frühen römischen Kaiserzeit: dynastische Legitimation, Victoria und Aurea Aetas, Jahrbuch RGZM 43/2, 1996, p. 383–475.

Lang, J.: Study of the Metallography of Some Roman Swords, Britannia 19, 1988, p. 199–216.

Lersch, L.: Das sogenannte Schwert des Tiberius, Bonn, 1849.

Lippold, A.: Zum „Schwert des Tiberius“, Festschrift des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums in Mainz zu Feier seines hundertjährigen Bestehens, vol. I, Mainz, 1952, p. 4–11.

MacMullen, R.: Inscriptions on Armor and the Supply of Arms in the Roman Empire, AJA 64/1, 1960, p. 23–40.

Miks, Ch.: Studien zur römischen Schwertbewaffnung in der Kaiserzeit. 2 vols., Rahden, 2007.

Mlasowsky, A.: Nomini ac fortunae Caesarum proximi. Die Sukzessionspropaganda der römischen Kaiser von Augustus bis Nero im Spiegel der Reichsprägung und der archäologischen Quellen, JDAI 111, 1996, p. 249–388.

Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of London vol. II: From April 1849 to April 1853, London, 1853.

Ritter, F.: Entstehung der drei ältesten Rheinstädte, Mainz, Bonn und Köln, BJ 17, 1851, p. 1–52.

Roach Smith, Ch.: Notes from a Journal of an Antiquarian Tour on the Rhine, The Gentleman’s Magazine 189, 1851, p. 42–50.

Scharf, J.: On the Manchester Art-Treasures Exhibition, 1857, Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire 10, 1858, p. 269–331.

Schumacher, K.: Kataloge des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums (Band 1): Verzeichnis der Abgüsse und wichtigeren photographien mit Germanen-Darstellungen, Mainz, 1912.

Senckler, A.: Mars Ultor, BJ 14, 1849, p. 65–73.

Strong, E.: Art in Ancient Rome vol. II, New York, 1928.

The Sword of Tiberius, The British Museum, Museum number 1866,0806.1 URL: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/G_1866-0806-1 (last accessed on 12th August 2024)

Walker, S.: Augustus and Tiberius on the „Sword of Tiberius“, in: Walker, S. - Burnett, A. (eds.), Augustus. Handlist of the Exhibition and Supplementary Studies, London, 1981, p. 49–55.

Walters, H. B.: Catalogue of the Bronzes, Greek, Roman and Etruscan in the Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities, British Museum, London, 1899.

Westgarth, M. W.: A Biographical Dictionary of Nineteenth Century Antique and Curiosity Dealers. Regional Furniture, Glasgow, 2009.

Yates, J.: Der Pfahl-Graben. Kurze allgemeine Beschreibung des Limes Rhaeticus und Limes Transrhenanus des Römischen Reiches, Augsburg, 1858.

Zanker, P.: The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus, Ann Arbor, 1988.

Released 27. 8. 2024